10 minutes

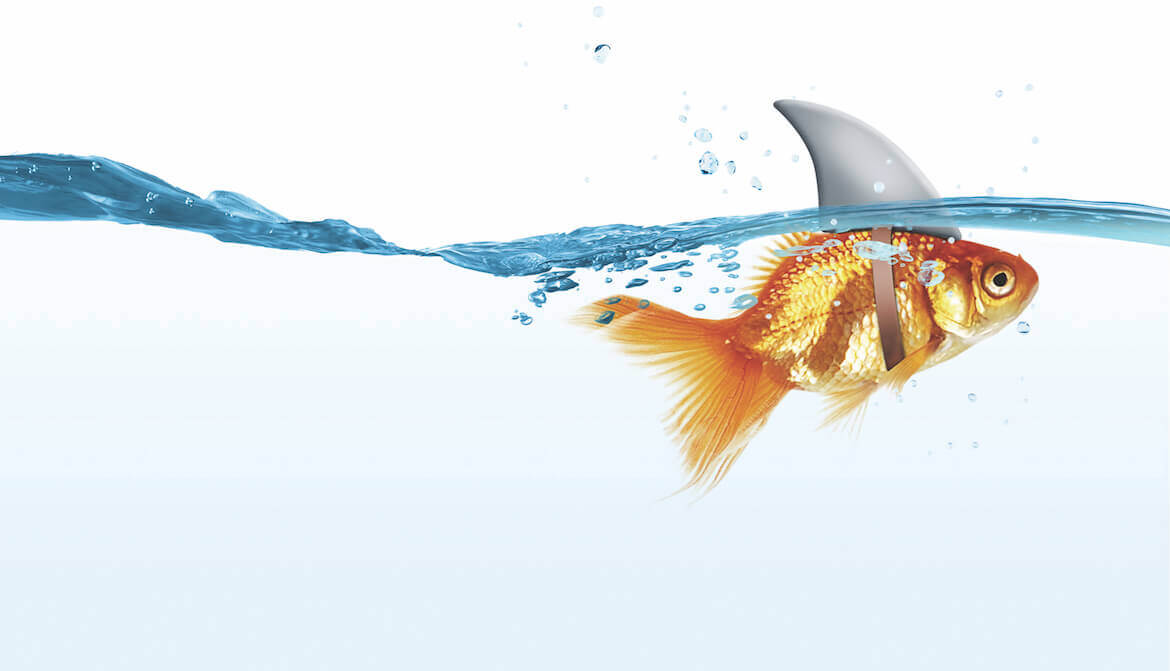

Small credit unions leverage partnerships and good strategy to strengthen our industry by serving members others overlook.

Teri Robinson is not just the CEO of Pacific NW Ironworkers Federal Credit Union. She’s also CFO, lender, marketing manager, HR specialist, compliance officer and IT help desk—though she admits her expertise for that final job was developed through trial and error and often boils down to advising, “Try turning it off and turning it back on.”

Most of all, “I’m an agent of change, and that’s exciting to me,” Robinson says. “We’re making stuff happen, and that’s why I love my job.”

Like many of her peers leading small credit unions, Robinson is a fierce advocate for the role of these financial cooperatives in the marketplace and their commitment to serving members. She joined the Portland, Ore., credit union in July 2009 as the lending administrator and became CEO eight months later. Under her leadership, the $26.5 million CU with 5,200 members has grown from 619 to 1,700 checking accounts.

That emphasis is a stepping stone to winning members’ loan business, she contends, but getting those primary accounts required the credit union to enhance accessibility. Pacific NW Ironworkers FCU maintains three branches, but more to the point, it was an early adopter of remote deposit capture, introducing the mobile service in early 2013.

“Our members are out on a job site when contractors hand them a check,” Robinson notes. “If people really dove into our numbers, they’d see that when we introduced mobile banking, that’s when we started to see loan growth.”

Key Partnerships

Robinson joined Pacific NW Ironworkers FCU as it—and its members—were coming out of the Great Recession, which required reducing expenses, asking vendors to work with the credit union, relying on support from partners like the Northwest Credit Union Association, and charging off some loans. The new CEO sought out secondary capital via loans from other credit unions and industry organizations to level out net worth and satisfy National Credit Union Administration capitalization expectations; 80 percent of those loans have since been repaid.

“We still wanted to loan to members and ask for their business, and the support of our board and members during those times made me trust our members even more,” she says. “We’ve refocused on engaging our existing members … letting them know we’re here to serve them rather than spending money to recruit new members.”

Robinson seeks out vendors that understand the needs of small credit unions, like its core provider, FLEX, Sandy, Utah, which helped Pacific NW Ironworkers FCU launch its mobile banking solution quickly. “We don’t have time for long processes to get a product like this up and running,” she notes.

She also forges partnerships with other financial cooperatives, like an arrangement with another small credit union, $22.4 million Register-Guard Federal Credit Union in Springfield, Ore. The partnership allows members to conduct simple transactions at each other’s branches through the Credit Union Reciprocal Transactions network, a program developed by smaller Oregon CUs to provide convenience without cost.

“We network with other credit unions, and we’re all willing to share our ‘secret sauce,’” she adds. “There are cooperative strategies from the ’70s and ’80s that are still relevant with a little updating.”

One update Pacific NW Ironworkers FCU has made is to convert its branches from transaction hubs to loan centers, with loan desks replacing teller lines. All eight employees double as loan officers, continually asking members for their business and mining credit reports manually for refinancing opportunities. The return on that strategy has been about $11 million annually in loan growth in recent years.

“Our industry needs to figure this out—that credit unions like ours are needed more now than ever,” Robinson says. “We help people that no other financial institution wants to help. A $250 loan doesn’t cost out for us, but that’s not the way we look at it. We look at (it as) offering our members a 12 percent loan versus a 30 percent loan from a finance company.”

Daunting Challenges

In the past, consumers selected their primary financial institution based largely on proximity to home or workplace, notes Glenn Christensen, president of CEO Advisory Group, Kent, Wash. Today, though, the many avenues available to access financial services are revolutionizing consumers’ preferences and expectations.

“These are probably the toughest times that credit unions have seen, in many ways, because of the new forms of competition, the advances in technology and the need for credit unions to respond quickly to those advances and to changes in member behaviors,” Christensen contends.

One of the biggest challenges for smaller credit unions is reinvesting in the growth of their organizations,he adds. “When their margins are thin, as they have been for quite some time, finding ways to reinvest for growth becomes a very difficult thing to do.”

Smaller credit unions that are thriving have leaders who apply a strategic mindset to explore how best to serve their members, Christensen suggests. “They can no longer afford to be all things to all people. They really need to be hyper-focused on particular market segments or product lines and try to carve out those niches that they can profitably serve.”

Formulating growth strategies can be particularly tough in sectors where sponsors or select employee groups have downsized. At the same time, credit unions have to keep pace with member expectations for ease of use set by retail giants like Amazon. Leaders of small credit unions rely on technology vendors and business partners to deliver those services, but they also need to develop their expertise “to understand the details of how this all works and how to position their credit union’s offerings,” he says.

| Daunting Future Forecast

Smaller credit unions that are thriving today must confront the continuing challenge to maintain profitability and resources to meet members’ long-term needs, cautions Glenn Christensen, president of CEO Advisory Group, Kent, Wash. The statistics on the ability of small credit unions to keep pace in recent years are grim: From 2010 through 2015, according to Christensen’s analysis, a strong majority of credit unions under $50 million in assets (72 percent under $10 million and 61 percent in the $10 million to $50 million range) declined in membership. In a forecast on the viability of credit unions based on asset size, Christensen reports that the current average size of the 2016 census of 6,022 credit unions was $219 million. In 20 years, based on the historical growth of assets and rate of mergers, he estimates that surviving credit unions will number about 3,300 with an average of $2.6 billion in assets. “That will be a very difficult market for credit unions to compete in,” he says. “The biggest credit unions will be able to provide extreme value through economies of scale. Even the most successful small credit unions will be challenged to maintain profitability and fend off threats such as cyberattacks … but some niche players will have a chance to survive if they stay focused and develop hyper-differentiated products.” |

Building on Strengths

CUES member Cisco Malpartida Smith became president/CEO of $10.7 million, 900-member The Florist Federal Credit Union in December 2016 with plans to build on its niche market—200 floral associations as well as retail florists, growers and nursery owners and their employees and families nationwide—and to strike out in new directions.

With its unique field of membership, The Florist FCU is rare among smaller credit unions in offering business services. About 40 percent of the credit union’s lending is with small businesses for floral delivery van loans, credit cards and lines of credit to support floral shop operations until accounts receivables come through, especially around big holidays like Valentine’s Day and Mother’s Day.

Most of the credit union’s interaction with members is online; its only branch in Roswell, N.M., serves about 40 members on a regular basis. One of Smith’s first orders of business was to deploy a new website (read more about it), internet banking and mobile services, all through Narmi, New York. Narmi was founded by Nikhil Lakhanpal and Chris Griffin, respectively the former CEO and CIO of Georgetown University Alumni and Student Federal Credit Union, a student-run financial cooperative Smith had mentored. The Florist FCU’s custom-designed online presence was cited by The Financial Brand as one of “20 Visually Stunning Website Designs from Banks & Credit Unions.”

Smith’s prior experience is with two large CUs, $17 billion BECU in Seattle and $1.8 billion GTE Financial, Tampa, Fla. At his previous post with GTE, his department’s annual budget was more than $1 million. In comparison, at The Florist FCU, “we count the individual staples. There is truly is no more to cut.”

“Small credit unions really excel in the service category. We know our members literally by name,” he notes. “But every day, costs go up. Every day, it gets harder as we deal with rising costs for compliance, talent, technology, service, marketing, cyber threats, and the list goes on and on.”

‘Scrappy and Bold’

Smith shares with his board and staff the goal of being “scrappy and bold,” looking to differentiate and specialize in developing new products and ways to improve service without increasing expenses. The Florist FCU has added a 50-state mortgage lending program, with Smith and CFO Kenn Bell in effect working as mortgage brokers, taking advantage of the credit union’s nationwide charter to lend with multiple national wholesale lenders. By adding home loans and stepping up business lending, the credit union has grown by more than 40 percent in just over 10 months and developed a significant new income stream, he reports.

“It’s a lot of work, but we realize that organic growth alone won’t be enough to survive. We’re looking for ways to reinvent ourselves,” he adds, noting the CU’s federal charter and nationwide membership as an advantage.

One innovative example is Smith’s discussions with a nonprofit organization that wants to create a nationwide financial cooperative, Equality Financial, a Federal Credit Union, to serve the LBGTQ community. Equality Financial could launch as a parallel brand under The Florist FCU’s charter and serve members through its existing online and mobile channels.

“In 29 states, it’s not illegal to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation, so gay, bisexual and transgender people face real barriers to obtaining financial services,” Smith says. Equality Financial could offer such products as adoption loans (see “Bridging the Gap for Adoption”) for same-sex couples and support for other credit unions in formulating policies for accepting proof of identity for transgender individuals in transition, for example.

“In talking to other credit unions, we hear people say, ‘We thought we were serving those members, but we realize now we need to revisit our policies and processes to be appropriately sensitive to the needs of the LBGTQ community,” he notes.

Other changes are in the works: The Florist FCU has doubled its full-time staff to seven and will be opening a management office in Seattle (in a free space offered by another credit union), leveraging easy access to the Seattle market.

Smith has heard the threshold of $1 billion in assets may become the watermark for survival. At the same time, he’s also seen the potential for small credit unions to thrive by targeting underserved rural communities and specialized markets.

“But we can’t just tread water. If we’re just surviving, we’re dying—and under constant threat from the rising costs of doing business or a singular event like a cyberattack,” he says. “Small credit unions can’t follow some generic strategy. We have to stay engaged and focused on the needs of members that others overlook.”

Karen Bankston is a long-time contributor to Credit Union Management and writes about credit unions, membership growth, marketing, operations and technology. She is the proprietor of Precision Prose, Eugene, Ore.