6 minutes

Being a consistently great lender requires a working understanding of economics.

In the past, I’ve joked about seeing myself as an amateur economist. I’ve also joked about how I’ve predicted seven of the last three recessions. Being an amateur economist, however, does have its advantages when it comes to risk-based lending.

What’s the Point of Risk-Based Lending?

Depending on your credit union, you’re probably driven to do a good job with risk-based lending so you can help more members and/or make more income. Helping more members normally leads to more income, so the two reasons have a closer relationship than you might think at first glance.

While making more income is important and the key driver for many credit unions, why do credit unions, banks and specialty lenders often get into trouble with risk-based lending? There’s no guarantee that you’ll always make money with it; when a recession hits, you’ll likely have 12 to 24 months of higher losses and allowance for loan loss expense. The result will be a period of lower earnings. The trick to risk-based lending is to make sure you made enough extra income between recessions, right? To be successful in risk-based lending, you must have a feel for when the economy might be ready for a recession.

Learn From Past Mistakes

Having been in the lending business for the better part of four decades, I’ve made a few observations about risk-based lending:

One: If you want to be successful in the long run, the loans you make at the end of a period of economic expansion (and closer to a recession) are more likely to have higher losses and potentially be unprofitable than loans you made at the beginning of the economic expansion. The market for these loans gets overheated and that leads to greater losses. More on that in a bit!

Two: The bigger national lenders and those companies that specialize in near- and sub-prime lending tend to do a better job of timing the market. This isn’t investing in a 401(k), where trying to time market peaks and valleys has proven to be of dubious value. You need to know when to get in and get out of the market, if not make substantive changes to your credit policy.

When it comes to “get in,” 2013-2014 is fairly fresh in my mind and worthy of discussion. The economy had improved, delinquency was down, and while the growth in gross domestic product wasn’t setting any records, the economy was on much better footing than in 2008-2011. The market for risk-based loans started to strengthen and, frankly, credit unions were slow to react.

Why is this important? Spreads over A loans were still high, and with five-plus years of economic expansion laying ahead, losses would prove to be low. The end result? Healthy profits if you were “in.”

Don’t Be Late to The Game

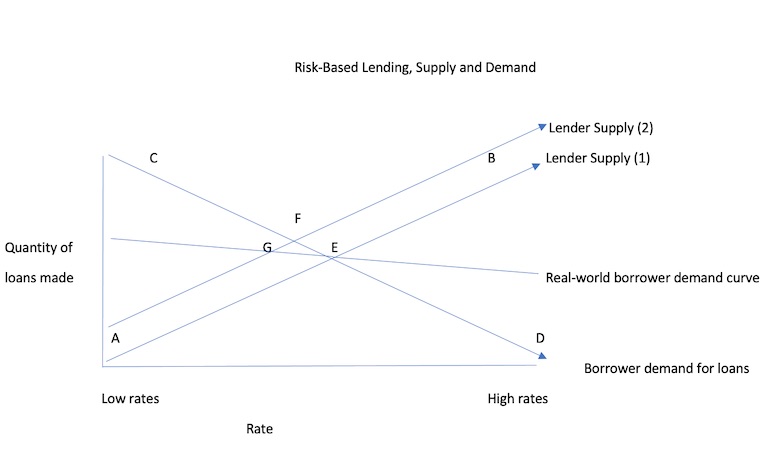

Here’s what an economist would have to say about risk-based lending when your timing is late: The law of supply and demand dictates your success as much as quality underwriting. The graph I developed shows the implications to supply and demand as they pertain to risk-based lending.

On the horizontal axis are loan rates and on the vertical access is the quantity of loans made in the market. Let’s look at the designated points on the graph.

“A” represents the amount of loans available in the market if rates are close to zero for lower credit scores. Low rates, and there’s no return to offset the great risk.

“B” represents the loans available in the market if rates are really high. Risk, but plenty of return!

“1” is the supply curve for loans in a normal market. This might represent a period of time shortly after a recession and as a recession appears more likely in the near future.

“2” represents the loan supply curve when the market gets heated up. More lenders want yield and they’re willing to take on more credit risk to get it. Those who remember college economics will recognize the upward shift in the supply curve. Lenders want more loans, and will increase their availability, regardless of the rate.

“C” represents how many loans consumers want when rates are really low. Show me the money!

“D” represents how many loans consumers want at very high rates. Even consumers with lower credit scores lose interest in borrowing at some level of rates.

This graph assumes that the demand curve for loans by consumers really doesn’t shift upwards as the economy improves. My experience is that B, C and D credit score borrowers are almost always in the market to borrow, and their demand for loans isn’t as variable as borrowers with stronger scores.

Let’s see what happens when lender demand for yield and the risk changes (shift in demand to supply curve 2). The equilibrium point in the market previously (point “E”) now shifts to point “F.” Equilibrium is where borrower demand meets lender supply, which sets the rates in the market.

So Why Is Understanding This Important?

Here’s the problem: In the chase for more yield and willingness to take on the losses associated with risk-based lending, more lenders in the market mean lower rates (moving from point E to F). It starts to defeat the purpose. Remember when I spoke of market timing? By 2015 I witnessed this in the marketplace, as rates for B, C and D loans were declining more than rates for A and A+ loans. The return for the risk (or risk premium) had declined.

Here’s the Kicker!

Admittedly, my understanding and recognition of consumer demand is a little fuzzier. Lower rates should encourage more near- and sub-prime borrowers to borrow more often. But it seems that these borrowers are always in the market—thus my “real world borrower demand curve.” You see, it’s fairly flat; B, C and D credit score borrowers are not that driven by rate under this assumption. Now look to see the intersection of the borrower demand and lender supply curves, “G.” Market rates have fallen even further! Now, this is looking really unattractive if your market timing has been slow.

The Final Gut Punch

Lenders are a stubborn bunch; if we decide to grow B, C and D loans and set a goal of 20% growth, we’re going to do what it takes. If borrower demand or loan application volume is fairly flat, chances are there won’t be enough good loans to go around to all of the lenders that want them.

Because we’re a stubborn bunch, guess what? We lenders will let our standards drop! If you’ve been in this business for any length of time and survived a recession, you know how to underwrite a B, C or D loan. In the quest for that elusive growth number, we’ll start accepting lower incomes, higher debts, higher loan-to-value ratios and longer terms. That’s how you can generate more loans if borrower demand doesn’t produce what you need; you simply approve a greater percentage of these loan applications.

In essence, what makes risk-based lending so painful in a downturn is the double whammy—not enough yield and significantly higher losses from lower-quality underwriting.

Supply, Demand and Economic Trends

I’ll freely admit that we lenders don’t get enough credit until a recession hits and our portfolios survive with minimal damage to the balance sheet and income statement. To succeed, most non-lenders would agree we have to understand marketing, business development, product design, member experience and sound underwriting. Now we can add a working understanding of economics to the list of what it takes to be a consistently good lender!

CUES member Bill Vogeney is chief revenue officer and self-professed lending geek for $8.4 billion Ent Credit Union, Colorado Springs.