5 minutes

Four ways savings products could change in service to your members

Credit unions serve as financial intermediaries to members who need money they don’t yet have (borrowers) as well as those who have money they don’t yet need (savers). As such, they are always challenged with adjusting pricing and value expectations to meet both sets of needs.

Today, after 30 years of ultra-low interest rates, rates are rising. That means credit unions must do some rethinking about how best to serve both their borrowers and their savers.

At the end of this article, you will find four specific ways handling deposits at credit unions could change as interest rates rise. Before we get to that, we’ll take a look at the rate changes we have seen so far and will see in the near future. I will state my case for why we are leaving the era of ultra-low interest rates behind for the foreseeable future.

A Recent History of Rates

Our media are currently flush with reports of the magnitude and evils of inflation. Over the past three decades, inflation appeared to be a thing of the past—a phantom menace.

The Great Recession was an economically induced financial crisis caused by financial mismanagement and overleverage. It was a long and painful recession with significant declines in real gross domestic product over two years. Recovery was slow and all the monetary and fiscal stimulus used at the time created little price instability to the upside. At this time, our economy experimented with and ultimately embraced low interest rates as a “performance-enhancing drug.”

Deflation was generally more of a concern than inflation in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Some economic participants enjoyed this era of low interest rates while others were forced to endure it. Savers were most punished, and no one seemed to care as time passed. It seemed that everyone embraced the narrative that low interest rates were now universally good for an economy.

In contrast to the Great Recession, we had a pandemic-induced financial crisis in the first quarter of 2020, and the economies of the world went into a steep recession. GDP fell and unemployment spiked at rates not previously experienced in modern times. Leaders responded with the performance enhancing-drugs—the low rates—that had been used in the Great Recession. This time, however, they didn’t test and learn. The economic response to the crisis was an immediate reduction in interest rates to the floor, unprecedented gigantic levels of quantitative easing and broadly distributed fiscal stimulus.

Leaders said they would do whatever it took to get us through this pandemic, and they walked that talk, leaving no ammunition unused. However, when so much was done that was never done before, we got some unintended consequences.

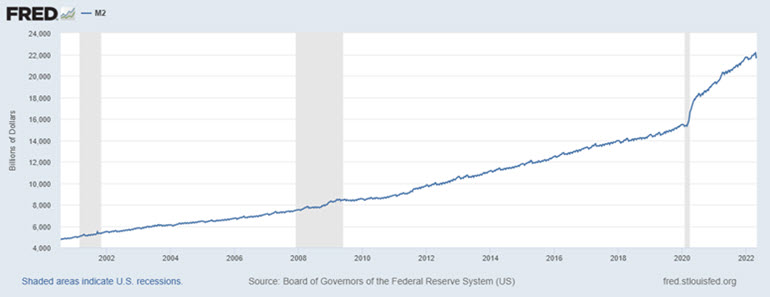

This graph of the M2 Money Supply tells the story of how we first experimented with monetary policy and quantitative easing during the Great Recession. You can see the money supply increase at an abnormal pace in 2009. Nothing like that can be observed in the previous recession of 2001.

But also notice the magnitude of quantitative easing in the very brief but intense recession of 2020. This gigantic spike in money supply has had significant consequences, much of which was unintended in terms of the magnitude of inflation.

The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate in its charter: full employment and stable prices. For three decades, inflation appeared to be benign, so the Fed gave its full attention to keeping unemployment low with low interest rates. Today, the board has no choice but to address the lack of price stability.

The levers they can adjust are overnight interest rates and quantitative tightening by selling the bonds on their balance sheet. Both policy tools will push interest rates up. In 2022, the bond markets have awakened to the reality that we are leaving behind the era of sustained ultra-low interest rates.

Action Steps for Credit Unions

Following recent Fed rate hikes, bank and credit union approaches to depositors so far have varied greatly. Some are in denial and suggesting that savers should expect no portion of the rate hike. Another group are saying “yes, but.” A bold and creative minority are embracing the opportunity to find ways to say “yes, and!”

Rather than try to discourage depositors’ expectations of greater value for savings, some financial institutions are embracing the opportunity to offer advanced savings products enabled by today’s technology and distribution options. Here are some of the changes in managing deposits that could accompany this rising rate environment:

- Member service representatives will have pricing and sales platforms that equip them to serve as financial professionals and trusted advisors who can help depositors better manage their money through emerging interest rate dynamics by instantaneously modeling simple yet more sophisticated savings offers (see next point). The posture of deposit order-taker and product pusher with a static rate sheet will soon be obsolete.

- There will be migration to hybrid savings accounts that give depositors high yields and short commitments and yet don’t give them all the optionality to open and deposit without some level of commitment to the broader relationship with the credit union. Today, 93% of banking industry deposits have no contractual maturity. The requirement for depositors to qualify for opening and funding these hybrid savings products will make these savings accounts a better deposit product for credit unions than high-yield money market accounts that typically give unlimited optionality to depositors. The industry has widely embraced simple savings offerings through the recent period of ultra-low interest rates. With all the optionality in the hands of the depositors, a financial institution is left in a very vulnerable position as rates rise.

- Rather than wait to maturity, consumer time deposits will be refinanced before maturity as savers are proactively approached by credit unions to trade out their existing time deposits for new ones with a clearly presented specific, indisputable, guaranteed and insured financial gain.

- Long-term savings will evolve into products that look more like mutual funds with daily redemption options rather than approaching savers with the notion that they must “lock up” their money with no realistic liquidity between now and maturity.

The changes coming in the industry will provide fresh value to those who have owned long-term savings through the drought of interest rates. The industry will undoubtedly find that fortune favors those credit union leaders who have prepared wisely and act boldly as interest rates rise.

Neil Stanley is founder and CEO at The CorePoint.